Fort Ticonderoga has a lot of history to tell. After all, it has been in existence, in some way or another, since 1755. It has seen occupation by the British, French, Germans, and forces of an emerging nation: the United States of America.

Today, you can visit the fort to learn all about that rich and complex history, but what makes the fort truly stand out as a special destination is the way that the past is brought to life. A visit to Fort Ticonderoga, nicknamed America's Fort for the role it has played in American history, is an exciting adventure in living history, full of cannon fire, demonstrations of daily activities, music, and more. You'll find more here than you might expect; here are four highlights that show some of the coolest things you might not have known about the history and activities of the fort.

A pioneering woman's impact

Once upon a time, Fort Ticonderoga lay in ruins. A family with a great interest in history bought the land, set about restoring the fort, and built an expansive summer home, named The Pavilion. In 1921, the family commissioned a young woman named Marian Cruger Coffin to design a garden at the estate. Coffin had studied landscape architecture at MIT, one of only four women enrolled in that co-ed program. At the time, most landscape architecture programs either did not admit women at all, or kept them separate from men. Coffin had a natural talent and after receiving her degree in 1904, established her own office as companies run predominantly by men wouldn't hire her. Coffin's family connections helped her get commissions and her high quality work made her a sought-after landscape architect of gardens for the East Coast elite.

Coffin’s designs were more complex than simply what plants to place or what might grow well on the shores of Lake Champlain; her designs incorporated every necessary detail, from the shape of the garden beds to the paths, woodlands, and, in particular, how plants would impact views and create backgrounds. Coffin didn't just create a garden, she created an environment.

Today, Coffin’s garden at the Pavilion is planted with more than 100 species of plants and flowers, per her original plans. Coffin's carefully laid paths lead visitors through the flowers, under flowering trees, and around fountains and benches. A tea house stands in one corner, a cozy spot to rest and admire the thousands of blooming flowers. It is a space to enjoy and live in. Years ago, the Pell family held luxurious garden parties here, with people such as Charlie Chaplin as guests. Today, visitors walk the same paths, enjoying the garden as Coffin and the Pell family originally envisioned. Special events, including garden parties and an annual heritage festival, are still held here, so you too can party like a vintage movie star.

Feeding an army

The gardens at Fort Ti aren’t all decorative; the first gardens at the fort were established in 1756 by French and Canadian troops to help feed the soldiers who were laboring to build the fort. While nowadays we take cars and easy access to grocery stores for granted, in the 18th century the fort was isolated, surrounded by wilderness, so the task of feeding everyone at the fort was a large one.

Because food quantities were so precious, during the French and Indian war of the 1750s, soldiers in the British and American provincial army had a weekly ration to live on:

- 7 pounds of bread (or flour for making bread)

- 7 pounds of beef or 4 pounds of pork (fresh or salted)

- 3 pints of peas or beans

- One half pound of rice

- One quarter pound of butter

Soldiers boiled their ration of meat so that they could drink the broth created, therefore not losing any valuable and much-needed nutrients. If you were lucky enough to be an officer, you received extra rations. Colonels, for example, received as much as six rations a week. In addition, French officers kept turkeys, while lower-ranked soldiers were occasionally permitted to hunt and fish the nearby woods and waters to supplement their monotonous diet.

Today, educators at the fort continue to plant vegetables that are appropriate to what would have been consumed in the past. Interpretive staff receive daily rations in the morning, some of it direct from the garrison garden, and cook their food in an earthen oven. The staff share information with visitors about their rations, why certain foods were available and others were not, and what it might have been like to eat pea soup every day for weeks or even months on end.

Today, educators at the fort continue to plant vegetables that are appropriate to what would have been consumed in the past. Interpretive staff receive daily rations in the morning, some of it direct from the garrison garden, and cook their food in an earthen oven. The staff share information with visitors about their rations, why certain foods were available and others were not, and what it might have been like to eat pea soup every day for weeks or even months on end.

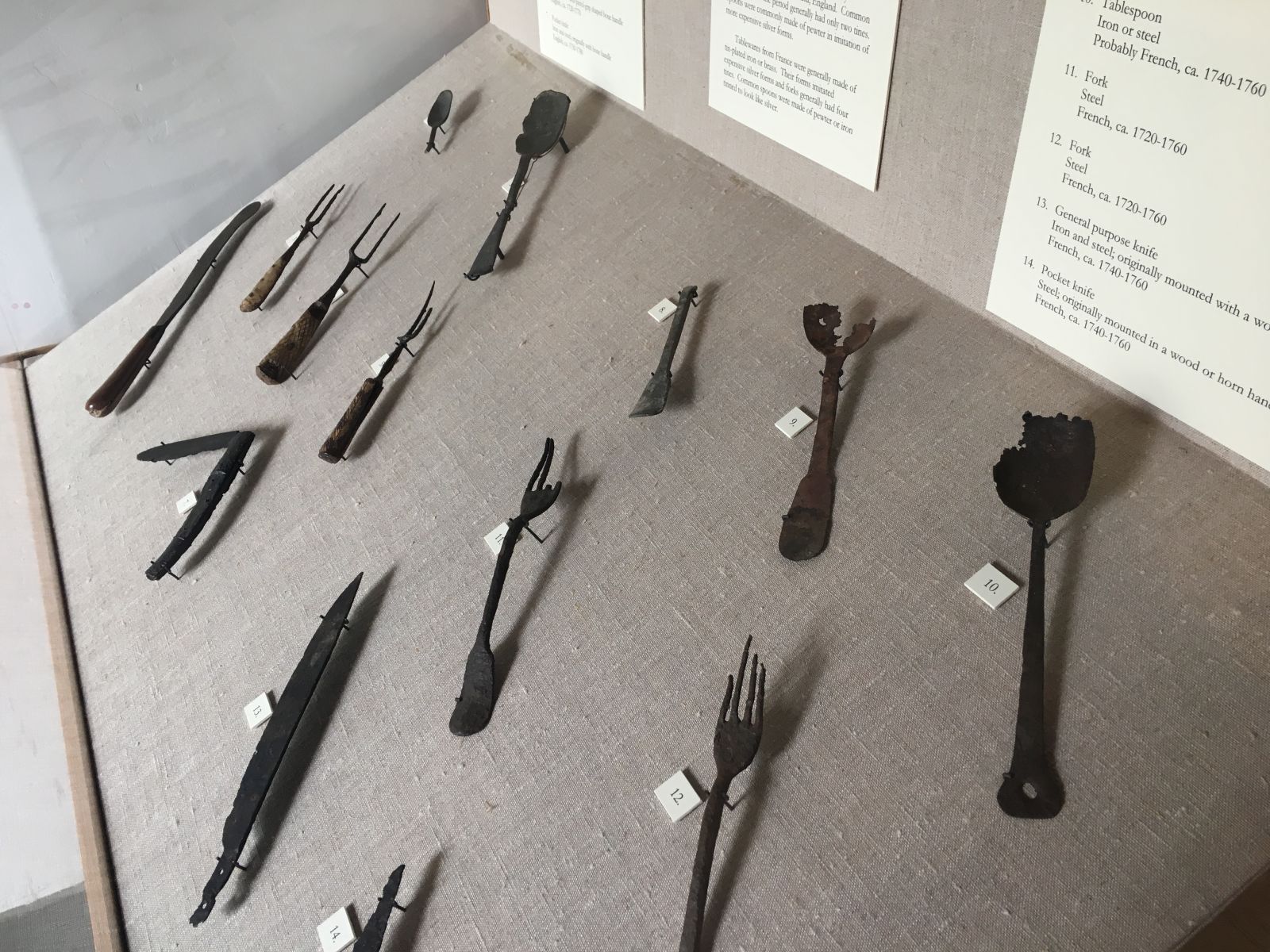

Although we probably take plates and utensils for granted nowadays, at Fort Ticonderoga your rank didn't just dictate how much food you received; it also dictated what you ate your food off of. Soldiers were responsible for purchasing their own plates, cutlery, and cups. On display at the fort are artifacts of such items that were found in archaeological digs on site; the displays range from inexpensive, crude cutlery to pieces of fine china plates and intricate wine glass stems, all of which would have traveled a long distance to get to the fort. The nicer the item, the more well off the solider who once owned it.

A not so merry Christmas

Holidays can be stressful; maybe you’ve had a Thanksgiving dinner that didn’t go according to plan, or one year the dog ate your birthday cake. Chances are, however, you probably haven’t had a Christmas as bad as December 25, 1776.

In 1776, some thirteen thousand men in the continental army were stationed at Fort Ticonderoga, holding off the British, who weren't quite ready to let go of the colonies. Despite their common cause, soldiers from New York and the mid-Atlantic states did not get along with the soldiers from New England. Because of this, the two groups were kept apart, with the New Englanders camped on nearby Mount Independence (now part of Vermont, but at the time accessible by a wooden bridge). Unfortunately, cultural differences got so bad that on December 25, 1776, a riot broke out between the two groups, drawing arms against each other. An officer from Pennsylvania led the attack on the Massachusetts encampment on Mount Independence.

Research indicates that, fortunately, no one was killed during the riot, although there were some injuries, and that the riot was quickly quelled. For a fort that has seen extraordinary conflict in its history, the Christmas skirmish of 1776 is surely one of the most unusual.

Handcrafted history

Strolling the grounds of Fort Ti, some of the most eye catching features are the many uniformed educators on the grounds, dressed in elaborate layers of wool, linen, and cotton, not to mention some amazing hats. Staff at the fort don't pretend to live in the 18th century, they really do it, through work in the shoemaking and tailor's shops. There, full- and part-time staff craft the garments that are worn by all of the interpretive staff, using traditional tools and materials. The fort's museum collection includes original garments from the 18th century; the staff study these garments to painstakingly create patterns which they then use to cut and sew all the clothing worn on duty.

Amazingly, some of the English factories which produced wool and other textiles in the 1700s are still in operation today, enabling the artisans to use fabrics that are appropriate for the period. A visit to the tailor shop gives visitors the opportunity to learn about these garments, 18th century fashions, and period sewing and crafting techniques. As an extra bonus, an array of garments hang on wooden pegs, available for visitors to try on and imagine themselves not as 20th century tourists, but as 18th century residents of the fort.

In the shoemakers' shop, each shoe is handstitched from hand-cut materials with period appropriate tools and thread. Much of what is known about the shoes worn in the 18th century comes from remnants found in digs at the fort, as well as in an usual place: the bottom of the lake. A shipwreck in Lake Champlain yielded a barrel full of shoes, enabling researchers to learn more about the shoes that were worn hundreds of years ago.

Visitors are encouraged to ask questions about the work done in these shops and can even try their hands at a bit of sewing or shoemaking to enjoy a truly immersive experience in the world of Fort Ticonderoga.

The Lake Champlain region is a place of great history and adventure; we hope you'll round off your Fort Ticonderoga adventure with stops at our restaurants and lodging options.